Bola Tinubu’s appointment of Professor Joash Ojo Amupitan, a Yoruba Christian from Kogi State, as INEC Chairman has stirred intellectual ferment—and deservedly so. In his essay: “New INEC Boss and Tinubu’s Visibilization of Northern Yorubas,” Farooq A. Kperogi, a very cerebral Nigerian professor in the US, frames this as part of a broader “Yorubacentric” project. He argues that Tinubu, mindful of regional sensitivities, chose a Yoruba from the North to give ethnic visibility without provoking outrage in the Southwest or alienation in other regions.

As a Yoruba person from Kogi State, however, I believe this moment is more than political calculation: it is an opportunity to reclaim identity, affirm belonging, and challenge the rigid boundaries that have long divided Nigeria’s political geography.

Can we nuance this further: Born Northern, Speaking Yoruba

Our identity as Northern Yorubas—from Kogi, Kwara, and other North-Central zones—is not a creation of recent political engineering. It is rooted in history, in migration and in shared governance. We are northerners by geography, by civic relationship, by institutional service. Yet many of us have lived in the shade of invisibility—too “southern” for the North, too “northern” for the Southwest. This ambiguity has cost us recognition, representation, and respect.

Chief Sunday Awoniyi, Joseph Aderibigbe, scholars, civil servants from Kogi and Kwara States, have proved repeatedly that belonging is more than a map. Their service under Sir Ahmadu Bello’s philosophy of inclusive northern leadership demonstrated that identity need not be reductionist. That legacy matters now.

Visibility as Double-Edged Instrument

Yes, Tinubu’s selection of Amupitan (and earlier, Bashir Bayo Ojulari, a Yoruba Muslim from Kwara as NNPC GCEO) can be read as a strategic move to illustrate ethnic breadth. Kperogi’s critique is that this is “visibilization”—the rising visibility of Northern Yorubas—but fashioned as part of a Yoruba statecraft. Indeed, politics in Nigeria often uses identity as both tool and symbol.

But the visibility is not only strategic; it is restorative. It is repairing erasure. It reopens the possibility that being Yoruba in the North is not a liability, but an asset in Nigeria’s diversity. It invites us to view inclusion not as concession but as recognition of reality.

The North’s Choice: Alienation or Integration

Farooq cautions that the North must resist calling its Yoruba sons “other”—that rejecting Northern Yorubas as southeast or southwest citizens is to fall into Tinubu’s ethnic traps. I agree. To do so would deepen divisions, not heal them.

The North has long claimed the mantle of plurality—of faiths, languages, traditions. Its moral authority to do so depends on recognising its own internal plurality. To reject the Yoruba-speaking communities in Kogi or Kwara as “outsiders” would betray that responsibility. It would fuel suspicion that identity, once rigidified by region or religion, becomes weaponised.

Merit, Identity, Nationhood*

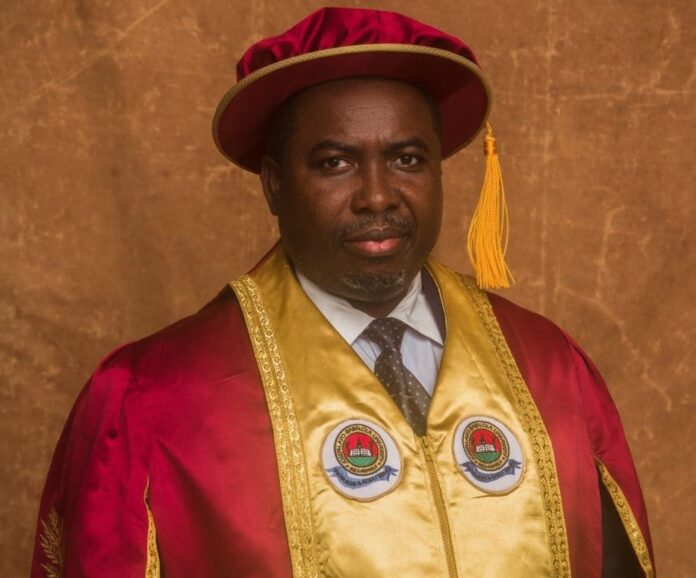

Amupitan’s appointment needs to be appreciated first for what it is: an appointment of a highly competent jurist, scholar, and Senior Advocate. His professional record makes him worthy of leadership. Ethnicity or religion should be context, not the totality.

At the same time, identity cannot be divorced from politics in Nigeria. The politics of ethnicity and geography are always present. But they should not be allowed to reduce the public conversation to divides. Rather, this moment should be a pivot: from seeing identity as a zero-sum game, to understanding how layered identities—northern, Yoruba, Christian, citizen—can coexist productively.

Towards an Inclusive North

If northern leaders embrace these appointments as belonging—not as tokens or southern implants—they affirm a broader, more inclusive idea of the North. One in which Yoruba-speaking or minority-language communities are not asked to choose sides or deny parts of their heritage.

This is more than emotional solidarity. It is political prudence. A region that denies its internal diversity undermines its own claim to moral leadership, weakens its cohesion, and devolves into suspicion and alienation.

Concluding

Let me affirm that Farooq Kperogi’s essay rightly surfaces important questions: whose identity counts, whose visibility, who gets to define regional membership. Yet as a Yoruba from Kogi, I see the Amupitan appointment as more than political signalling. It is a mirror held up to Nigeria’s unrealised promise of belonging.

Let us not allow this moment to be reinterpreted through rigid ethnocentric lenses. Let us instead treat it as an invitation—to rebuild national consciousness, to acknowledge layered identities, and to reclaim our place in the North not as “southern Yoruba” but as Northern Yorubas—neither borrowed nor alien.

Nigeria’s unity will not be secured by rigid regional fences, but by the willingness to see diversity within, and to accept that identity is not a monolith.

In that acceptance lies the foundation for a more inclusive and resilient nation.

Shalom. Peace.

Abanida is a physician/public policy enthusiast, OkunYoruba from Kabba/Bunu LGA, Kogi State, North-Central Zone, Nigeria.